Monetising India 2: Modern Retail and SuperK’s Secret Sauce

A deep(er) dive into the business model of SuperK

One of the reasons I love writing is because of the kind of conversations it enables. Over the past year or so of this newsletter, I've had the chance to speak to lots of talented people from across the product ecosystem - from operators to founders to VCs. The consistent feedback I get is that this newsletter has given them a fresh perspective on the Indian consumer, and also that it has made it easier for some founders to explain their thesis to stakeholders. (Grateful to all of you for taking out the time to chat and giving me this feedback - it keeps me going!)

The previous article on SuperK had a similar outcome - I had a chance to speak to Anil and Neeraj, the co-founders of SuperK about their business model. While the previous post talked about the consumer demand side (how premiumisation is eating into the kirana model, and how SuperK is exploiting the space), this one goes deeper into the retail space and why SuperK thinks it can win.

TL:DR

There is a trend towards organisation in food and grocery retail.

Some part of this is driven by aspirational consumer demand for better prices and products, more selection, and an overall better shopping experience.

Some part of this is also because MT has higher efficiencies on the supply chain and hence higher margins.

A combination of demand and business model means that kiranas will transition to modern format stores.

What happens to the kirana owners then?

This is where SuperK steps in with its value stack to help entrepreneurs run modern convenience stores, and helps them make more money than if they had a standard kirana.

What does the retail sector in India look like?

To understand how SuperK makes money, we need to start with the mechanics of the current Food and Grocery retail in India. (we will leave out other large verticals like apparel and electronics where the supply chain metrics are different).

Note: I will be oversimplifying in places for brevity - please excuse any small gaffes. If there are big gaffes though please do reach out to me and I will be happy to update my understanding (and the post).

2 quick definitions which will help you appreciate the rest of the post.

Traditional Retail (unorganised) - Mom and Pop Stores - cover 95% of the retail market in India. Also called General Trade (GT) or Kiranas.

Modern Retail (MT) - larger modern stores.

Here’s a graphic that breaks down the modern retail sector further. The key difference in format is store size. Store size determines the category mix, and therefore how consumers think about visiting these kinds of stores (you visit a convenience store at a higher frequency, and a hypermarket at a lower frequency because of the types of products each stocks).

Where does SuperK fit?

SuperK positions itself towards the lower end of the modern convenience store in terms of size (approx 500- 800 sqft). According to Anil, they want to position themselves as ‘New Modern Trade’. Imagine a kirana upgrading to a modern format. This also means that they focus on fast moving products, and have an emphasis on fulfilling a neighbourhood's requirements.

Modern Retail is expected to take share from unorganised retail over the next few years

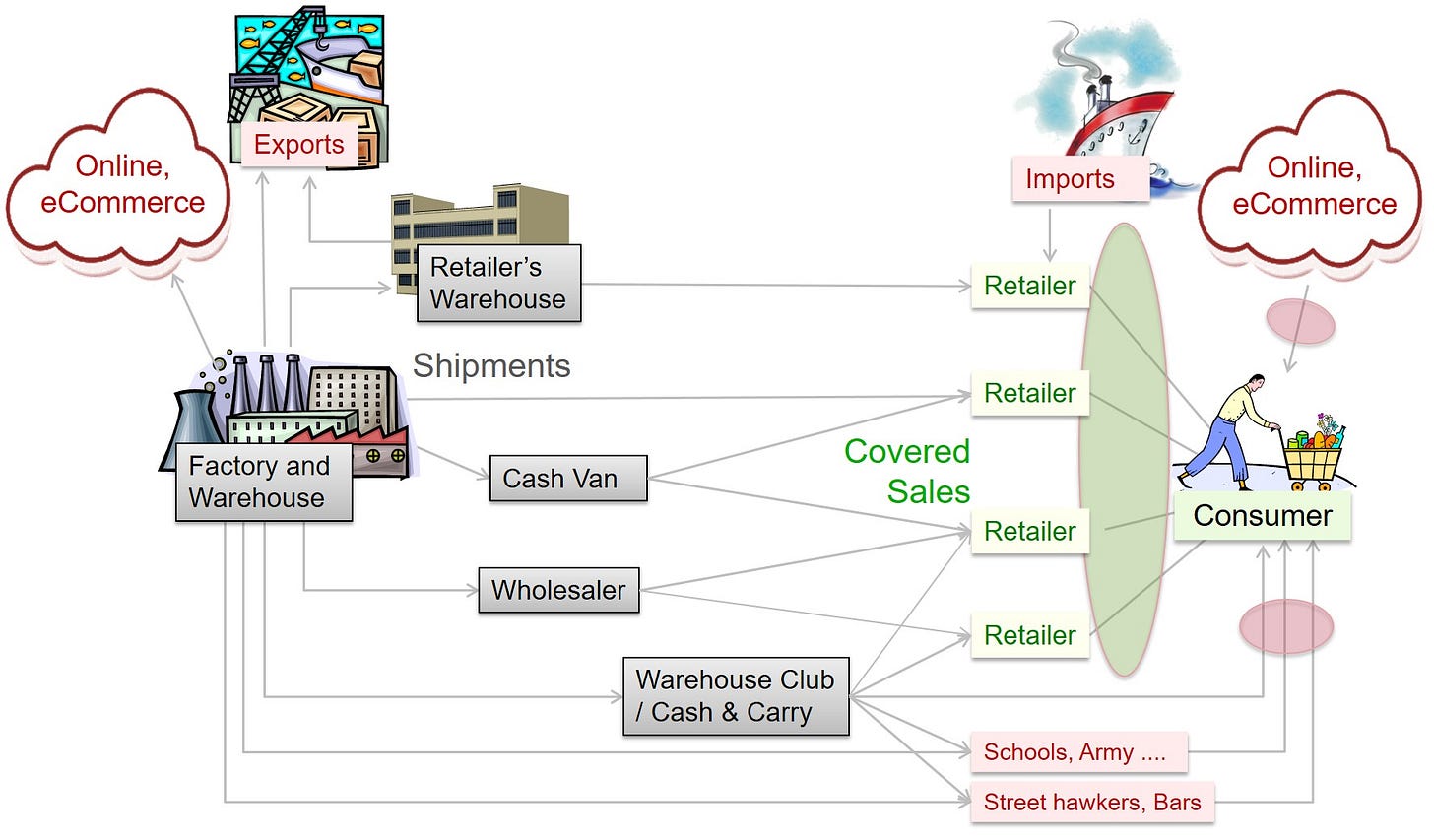

Now that we have broken down retail distribution into Traditional (kirana or General Trade GT), and Modern Trade (MT), let’s talk about how grocery items get to the retailer. This section will help us understand how the business model of MT and GT differs, and how this difference helps SuperK find a Go To Market wedge in the crowded retail space.

Distribution: How products get from factory to you

Important note: All margins mentioned below are gross (unless explicitly stated otherwise), i.e. what the customer pays minus the cost of the product (which the retailer pays to the distributor). To get the retailer’s actual take home, you have to subtract his costs like rent, salaries, and operational leakages.

The distribution leg of the supply chain involves transporting the goods from the manufacturing units to warehouses to various retail outlets, including supermarkets and traditional stores. Typically, manufacturers do not involve themselves in all the steps that are required to get a packet of noodles from their factories to your neighbourhood store. There are a few reasons for this, covered below (not exhaustive).

Specialisation: Manufacturers are good at manufacturing, and the skill sets that make you good at production are wildly different from the ones that are required to build a good logistics network.

Cost: It’s cheaper to outsource. This includes the cost of transportation vehicles, warehousing, advanced logistics systems, and personnel. Outsourcing allows manufacturers to avoid these large upfront costs.

Geographical spread: In a country like India, consumers, terrain, roads, languages, governments, all of this changes every 100 or so kilometres. This means a large centralised entity (the manufacturer) will lose out to local distributors and wholesalers who have better local understanding and established networks.

So there is a vast network of different types of distributors (I use the term loosely) which are integral parts of the retail supply chain. Their role is ‘breaking the bulk’ i.e. taking large volumes of products and breaking them down into chunks which are manageable for the next leg of the supply chain, and cumulatively getting the products from manufacturer to the consumer.

Here’s another way to visualise this. Your local shop owner is not lining up every morning at the gates of the noodle factory to get 100 packets of noodles to take back to his shop and sell to you. This is terribly inefficient for the shop owner and for the factory (also there is no noodle factory within travelling distance of every retail shop owner).

A factory which produces 10 million units of X has a few large distributors (imaginatively named Carry and Forwarding Agents - C&FA), who line up at the factory gate and buy large quantities of X. Lets say there are 10 C&FAs, who each buy 1 million units. They store the goods safely, and then forward (‘carry’ and ‘forward’) them to the next link in the supply chain.

The next link is usually smaller (Super Stockists, Distributors), and maybe want only 0.1m units of X. The bulk is broken here again as each C&FA splits its 1m units into smaller lots of 0.1m units for the distributors.

And so on.

This chain stretches all the way to the guy on a scooter who brings the 100 packets of noodles to your neighbourhood retail store.

Clearly, this process takes a lot of money and time (and you’ll see why this is important later). As compensation, each participant in the chain takes a piece of the MRP that you pay to the retailer as his margin.

The image below is a great representation of this supply chain, and the margins that each player in the chain makes.

Why is Modern Trade a better business than General Trade?

Lesser steps in the MT supply chain means more margins for MT retailers: Large modern retailers have the ability to procure directly from the manufacturer (because of their larger scale, see above image), leading to a lesser number of participants in the supply chain to share the MRP with, and hence higher margins for the retailer. However GT retailers have to go through anywhere between 2 to 4 steps to get the products leading to a much lower margin (see image above). The more the number of steps from manufacturer to retailer, the higher the price that the retailer has to pay. For example, something which you buy at an MRP of 100, the MT retailer is buying the product at 80 and making a margin of 20%, but your local kirana is buying the product at 90 from a distributor who has added his markup, making a margin of only 10%.

Manufacturers have better access to the customer in MT: Let’s say the manufacturer sees that a product is not being sold (and hence is not ‘fast moving’ enough) in retail stores. (This is a big problem in retail because inventory takes up shelf space which is constrained, so retailers want to make sure ‘products fly off the shelves’ so they can stock items again. This is why sales per square feet is an important metric in retail, used to judge public retail companies). So now, the manufacturer thinks of running a discount on the product to increase sales and recover some part of the cost. In the GT world this is painful. You have to print the discount, then you have to push it through the long supply chain to get it to the store and hope it is visible to the consumer via the retailer. (According to Anil, this process could take as long as 9 months!) However, in Modern Trade, discounts can be enabled centrally at checkout through the centralised POS terminal - leading to more sales per sq ft of shelf space. This is faster, more efficient, and saves time and money for the manufacturer. As Anil puts it - ‘The cost of making a mistake for the manufacturer is lower in Modern Trade channels’.

For the consumer, products are cheaper in supermarkets (what!): MT has higher margins and better access to the customer. This means they are better placed to run discounts and offer better prices. For example, they can run their own discounts (share some of their high margin with the customer) or the brands discounts (brands have shorter supply chains to customers and can communicate faster). This means better discounts, more sales, more inventory turns, more efficiency on the retailers fixed assets all of which can be passed on further to the customer in the form of further lower prices. All of this churns together in a nice virtuous cycle.

If MT is so much better, then shouldn’t General Trade transition to Modern Trade over time?

Very broadly yes - GT should transition to some form of MT, and SuperK is banking on this wave.

Note: The qualifier of ‘some form of MT’ is important.

Today 95% of Indian F&G retail is unorganised, while in developed markets this number is in the low single digits.

Closer home in Thailand, retail has transitioned from mom and pop stores to modern formats and contributed to 16% of GDP in 2019, second only to manufacturing.

Previously, the Thai retail sector had been dominated by small, family-run grocers which obtained stock from middlemen and distributors. However, the situation has changed considerably and retail store formats have transformed to modern stores which are less dependent on wholesalers. Operators are typically large-scale and now own extensive branch networks, and have favourable bargaining positions when negotiating with producers and wholesalers … adopt a range of innovations, including shop & stock and distribution management systems, distribution centres, and the widespread use of technology to help with a range of tasks.

In India, consumers want a better shopping experience provided by supermarkets, where the prices are lower, and the business model for the entrepreneur is better. DMart’s growth and Reliance’s long term ambitions in the space are testament to the potential of modern retail.

But India is a large country, and there are many ways to approach how this ‘organisation’ of retail will take place.

SuperK’s wedge into the organised retail space is centred around 5 themes.

Going Bottom Up and Penetrating Underserved Areas

SuperK is organising grocery in Tier 3+ towns, with small format stores with an average size of ~500-800 sq ft, which are at the lower end of the size of modern convenience stores. Smaller stores mean it is cheaper to set them up, easier to find franchisees to make the investment, and more franchisees means they are easier to scale.

This is very unlike traditional Modern Retail, which is dominated by large format stores which have predominantly grown in metro and Tier 1 cities, and are heavy on capital expenditure because of the store size.

Single store GT margins to Multi store MT margins

Once we start to visualise SuperK as an offline mini supermarket chain, the SuperK franchise goes from a collection of 10% margin GT stores, to a semi centralised modern trade player with margins of 20%, with a strong brand presence in specific geographies. Apart from all the supply chain advantages that MT has (which we discussed in previous sections), SuperK also has additional advantages in negotiating with brands on margins, standardising procurement, warehousing, running store specific pricing, targeted discounts, along with providing access to a wider range of products to keep up with evolving customer tastes.

Franchise model leads to better cost structures than most Modern Trade operations

Additionally, the franchise led model of SuperK has a cost structure advantage over MT.

According to Neeraj Menta (co-founder), “While the margin structures for Modern Trade are better than GT, the cost structures are worse. For example most MT players have > 7-8% store operations cost (Rental + Employees), the kirana guy would limit such cost to < 3-4%. Also, while the margin is higher there are also additional supply chain costs for the MT players as the stock is delivered to a single warehouse.” (and then needs to be shipped further to retail stores)1

“In the case of SuperK, the store operating cost is similar to or slightly higher than the GT cost structure because of the franchise led model, where the owner ensures everything is managed at the lowest cost possible. For example signing leases in the cheapest manner, and employing people from their known network for low cost. They work 365 days themselves and hence avoid the need to have multiple store managers. They also have a sharp focus on reducing frivolous expenses like switching off lights and fans when not necessary. This all ensures that the overall cost structure of store operations of a SuperK store is lower than a comparable MT store.”

1Neeraj explains that the exception to this is DMart which keeps its operational cost low by using its own stores and supply chain costs low by using their stores directly as warehouses (so there is no cost to ship from warehouse to store.)

Value Added Services

I have talked about this in the previous post. To run a low margin business like retail and to actually make money involves non trivial skill - which SuperK’s value added services help in providing. Standardising operating SOPs all the way from store set up to check out processes go a long way in adding efficiencies (and hence margins) to the store profile.

Proprietary Tech

All supermarket chains have some sort of tech in their backend, focused on optimising the supply chain costs, keeping track of inventory and sales, and other operational nuts and bolts.

According to Anil though, tech is where SuperK has an added advantage.

“We are the only offline supermarket chain that can run customer specific offers.”

What does that mean?

Retailers offer discounts to increase sales. However discounts are not very efficient. As a retailer, you never know if the product you are running a discount on would have been bought by a specific customer even without the discount. So you might just be increasing sales without adding new customers, and leaving money on the table.

So it follows that the most efficient way is to offer a discount only to those customers who would not have bought from you otherwise.

This is the big advantage that large e-commerce players (eg: Amazon) theoretically have. They can use all the data you and hundreds of millions of customers give them everyday to hyper personalise offers, and target discounts only at those users who wouldn’t have bought without the discount using the proprietary real estate of their mobile app.

Can you do personalised discounts in an offline store though?

In the offline world however, this practice of customer specific discounts is not prevalent. The strategy has always been to build a retail brand with an overall positioning, for example, on price. DMart’s positioning is ‘I will give you the lowest possible price across a large variety of items every day’. They optimise store size and operations to make sure they deliver on that promise. But nowhere in a DMart can you see an offer that is tailored to you. This works for the store - DMart carries a number of brands, and can vary the proportion of what they stock based on customer demand and how much margin the brand is willing to share with them (hence maximising their margins). But it doesn’t necessarily work for the brand. If you’re a brand and you run a discount for DMart stores, you never know if you’re going to get net new customers or just juice sales from existing customers.

SuperK does things a little differently.

Yes, they have all the POS, inventory management, and logistics tracking tech. But what they also have is a recently launched consumer app. The app is integrated with their POS data, and delivers customer specific offers before store visits. So I can look at the app on the way to the store, and see which staples product I have a large discount on, and pick that item from the store, irrespective of whether the discount is printed on the item or not (the POS will add the discount for me if I am eligible).

Here’s an example of how this tech helped.

A well known cooking oil brand (lets call it X) wanted to increase their market share in a geography serviced by SuperK stores. They also wanted to make sure that they take market share away from one of their competitor brands. SuperK worked with the brand to set up offers specific to the buyers of the competitor brand ONLY. Brand X went from 600 customers to 6800 customers, and 1,100 pieces bought to over 13,000 pieces bought. Staggering numbers. Now this means SuperK can now negotiate better margins with the brand, and continue to offer better prices to their customers.

Aside:

If SuperK can do customer level personalisation in a store, can’t DMart do this as well? Surely they have enough data.

Yes they can, but -

a) DMart’s specialisation is super low cost operations, not personalisation tech.

b) DMart are not going to be in the same markets and have access to the same customers that SuperK does. (an added benefit of SuperK’s GTM)

To recap, SuperK’s strengths on the business side lie in

Go To Market: Expanding in underserved areas like Tier 3 towns, in an asset light model, with a store size that makes sense for those geographies.

Margin Profile: Transitioning from a collection of GT stores with low margins to a semi centralised MT chain with higher margins.

Cost Structure: Franchise operators run the store frugally, resulting in lower costs than MT

VAS: Value added services to help franchise owners with the nuts and bolts of the business.

Technology: Proprietary tech, an example of which is running customer specific offers in offline stores.

Who are the entrepreneurs who want to run SuperK stores?

Those who want to become SuperK franchise operators are looking for independence and control over their life, while still earning money.

Students who have just graduated or those who have done a year or so in their first corporate job and realised that they’re not getting paid enough or want to be closer home.

People previously in sales roles and have some customer facing experience

People who have worked in a supermarket before and are somewhat aware of the mechanics of the role.

How much money can a franchise operator make?

To answer this question we have to understand the current options available to a potential franchise operator.

Start his own kirana - He likely has a small space of his own and some initial capital to buy inventory (which is why he is thinking of this business in the first place - ‘dukaan khol lete hai’). But there is a significant underestimation of the challenges. What should he buy and store? How much? Since he is at the bottom of the supply chain he sees the lowest margins of around 8%. Within this margin he has to factor in his rent, inventory costs (cost of goods unsold or taking shelf space in lieu of products that could have moved), operating costs (salaries, marketing), live with competition, and is at the distributor's mercy in terms of what products he can source. It’s not a predictable business, and one bad month can force him to shut shop and liquidate inventory.

Set up his own supermarket - This is out of reach for most people because of the large upfront costs. My research suggests that to set up a modern convenience store of around 1500 - 2000 sq ft needs ~INR 1cr in capital. However margins are higher at around 10%, but so are costs. According to Anil, for a monthly GMV of ~15 lakhs, a standalone supermarket needs 4 people (1 for billing, 1 for inventory, and 2 for packing and cleaning staples)

Work with SuperK - This combines the cost advantages of initial set up (franchise operators have their own space or have the capital required to invest in smaller spaces), along with the operational efficiencies of a supermarket. Costs to operate a SuperK store are much lower - to manage a sales volume of INR ~15 lakhs, they only need to employ one person, because most of the heavy work on sourcing, inventory packing, and to a certain extent even marketing (see the section on their tech above) is done by SuperK. This translates to higher margin, and higher take home. Anil shares that SuperK stores can make around 10 lakhs as monthly GMV, and of that the franchise operator can take home Rs 50,000. This translates to a take home rate of 5+%.

All these efficiencies show up in SuperK’s growth so far

Number of towns/villages ~ 80 (Source: ET)

Number of stores ~ 125 (Source: ET)

Average Store size: 500-800 sq ft

And now with additional capital, they have set their sights higher

In the next 2 years, SuperK wants to be in ~350 towns across their core catchment areas of Andhra and Telangana, increasing their stores to ~500. This translates to around ~550-600 cr INR in GMV ARR (run rate).

For comparison, Ratnadeep Retail (~25 year old supermarket chain), which operates 151 supermarkets (avg size ~2000 sq. ft.) in Andhra Pradesh, Telangana and Karnataka had an operating income of ~1400 cr INR in FY ‘23. (source)

Concluding Thoughts

As I’ve always said (and maybe too many times), retail is a sector which figures out where consumer tastes are heading earlier than everyone else, and SuperK is a business we should be watching with interest.

Something like the perfect storm is brewing in retail for India 2. Aspirational consumer + disposable income + modernisation + smart entrepreneurs = a transformed retail experience. With a lot of growth in organised retail coming from regional markets, SuperK has positioned itself well to ride this transition with a differentiated go to market and a working business model to become a large regional retail player.

Until next time.

Notes:

Two competitors I came across during this research

ApnaMart - Their pitch seems to be very similar to SuperK (from their website). The key difference that I could spot is that it is focused on a different geography (the eastern part of India, Tier 2 towns like Jamshedpur, Ranchi, Asansol). It has raised 14m USD so far from investors like Accel and PeakXV. This video gives an insight into their operating model.

Rozana - Their website explicitly says ‘social commerce for Bharat’. It appears to stay away from the ‘franchise store’ model and focuses on P2P selling instead. From their website ‘Rozana.in is a P2P rural commerce startup that leverages Tech and Data Science to cater to unique local demands of 1 billion Indians outside the scope of online commerce.’ Rozana recently raised 22.5mn USD from Bertelsmann India and Fireside Ventures.

References

Definitely an interesting read

Thank You