One Hundred Indias and The Lure of Lokal

Note 1: The roots of this mammoth post lie in a conversation with Vivek Raju and Rohit Kaul (facilitated by Sajith Pai) at the recent Blume Bash in Delhi NCR. Thank you folks for getting the grey cells buzzing!

Note 2: This is the longest article I have written in The Indian Pivot’s relatively short lifetime. (so click on the heading and open in browser). It takes a lot of detours, is not the most compact, could have been shorter, but it was a lot of fun to write. So <shrug>.

Before we start, an ode to longform

(this is one of the aforementioned detours. Yes, already.)

Call me old school (and I am 'old'), but I have a thing for long form text.

I think it's a product of circumstances. I remember hours spent digging through the book trunk we had at home (yes trunk, not shelf), trying to find something to while away time after school in the hot Delhi summer in the late 90s - a time without the distractions of the internet or mobile phones and thus singularly suited for this kind of pursuit.

Those hours yielded some weird/eclectic/absurd gems (at least for a 10 year old). I attempted The Fountainhead, and having never been exposed to a story starting with a naked man jumping off a cliff, gave it up. Ayn Rand gave way to Dominique Lapierre and his seminal Freedom at Midnight, definitely not recommended reading for a 10 year old, and then on we went to the school library, where, armed with borrowed library cards, I made sure I always had one unread book at hand at all points of time. Through all this I consider my crowning achievement to be the devouring of the Lord of the Rings trilogy during one fevered all nighter post my Class 11 school exams. (And may the IIT coaching gods forgive me for replacing HC Verma with Tolkien).

Short form content is a different beast.

Humans have short attention spans. In the grand scheme of things, we’re not that far removed from monkeys. The new and shiny thing has always been more appealing. (Who remembers Vine?). Now you have the availability of the internet in your pocket, and its so easy for your brain to default to 'open Instagram → browse for 5 minutes'. This is also the path of least resistance, there is no decision making required. 'What should I watch? How long is it? Do I have that much time?' - All of these questions melt away in the 30 seconds it takes for the short video to give you a dopamine hit.

And now we’ve moved on to different platforms feeding us different kinds 30 second dopamine hits. Instagram is for entertainment, and LinkedIn is for short form informational content - everything from product management tips to deconstruction of businesses and startups.

The 'LinkedIn emoji filled what's the takeaway' form is great for 'informational' content, and breaks the monopoly that traditional business media had on business knowledge. Why should business knowledge be couched in the obscure language of financial newspapers?

But knowledge is not insight.

define: meander (n) - (used about a person or animal) to walk or travel slowly or without any definite direction.

How do you really know things?

Depth of knowledge comes from meandering. That means immersing yourself in a topic, walking randomly through it, and exploring its nooks, crannies, and crevices. (This is commonly abstracted as 'first principles thinking' - understanding the fundamentals of a problem and breaking it down into its core constituents). But it's really unlikely that consuming 500 word content on your favourite social platform leads to insight, and it is even more unlikely that the insight is differentiated.

And hence, longform.

More specifically, I make a case for the type of writing that I have admired from afar, a great example being Eugene Wei's Status as a Service - a one stop shop for any builder who wants to understand the mechanics of social status in the digital age.

Undertaking an endeavour of that breadth and depth is beyond me today. But, as a proponent of human endeavour, I yearn to try.

So today, we will talk about a 100 Indias.

I will attempt to tell you a story, about how the length and breadth of this great country lends itself to a certain kind of business. We will take plenty of detours along the way (remember, meander), but hopefully at the end of it, you, dear reader, take away something of value. If you don't, there's always any number of podcasts and summarising tools that can help you out :)

TLDR

The theory of product expansion talks about finding a homogenous market with a problem that you can solve 10x better than the incumbent, and then expanding to the next adjacent market.

If you're building a consumer product for India, this is tough. The obvious go to market customer is the homogenous Tier 1 city resident. He speaks English, pays income tax, and transacts online frequently. But once you saturate this audience, you have to think about your next set of users, who are diverse across language, location, user behaviour, serviceability and more. It feels like building a new product altogether, and this is where a lot of companies get stuck.

Very few companies have taken the opposite path - i.e. choosing to build for the diverse and heterogenous audience in India first. They do this by finding the lever of commonality that makes most sense. For example, ShareChat did 'regional language content', using language as the atomic market.

Lokal is trying something harder - using 'demand for hyperlocal content in a district' as the atomic unit. Why does Lokal exist? What are the drivers for the demand for hyperlocal content in India? The answer to this last question is, IMO, the meat of this article.

100 Indias

Here's Jani, co founder of Lokal.

"If you take the context of India, with every 100 kilometre radius, dialects change and to an extent even language changes and of course therefore the cultural habit too.”

India is actually a 100 Indias. For people in the tech bubble of Indian metros, this is not obvious.

This is because the narrative in the tech ecosystem is almost always around businesses which serve India 1. This is where there is clear money to be made, with a decent set of successes that can be talked about.

Also, building for India 1 is comparatively the easier (and hence obvious) thing to do. If you're building for someone who is English speaking, earns a salary, and lives in a large city, you have a homogenous, large customer base, which is serviceable monetizable. As a founder you would be stupid if you didn't start your GTM with this audience.

But, what next? Beyond this audience, diversity kicks in, hard. Suddenly the words in our national anthem - Vindhya, Himachal, Dravida, Utkal, Banga - start to become very very real.

Crossing the Chasm

The theory around product expansion states goes something like this - Step 1 is figuring out your initial 'product market fit'. After this, to expand, you find an 'adjacent' market, update your product offerings, and go to market again, repeat ad infinitum.

The definition of adjacent is important - an ideal 'adjacent' market has 1 degree of separation from your current market.

This degree of separation could be along different axes - maybe you need to add to your product, but your business model, distribution, operational set up all remain broadly the same. Or the product remains the same, and you work on a new distribution channel to reach the adjacent market. The idea is to minimise changes to your existing PMF set up.

Sounds good, but here's the catch for builders in India - the moment you step away from the homogenous India 1 consumer, you have to deal with more than 1 degree of separation.

For example, the user's language is different. This means you have to rethink your marketing messaging and how the product communicates to the user. If the location of the user changes from a dense city to a sparse Tier 2 town, and you're delivering a physical product or service, it means rethinking your entire supply chain.

So moving from homogenous India 1 to heterogenous India 2 is almost like building another company (at the extreme). This is not easy, and hence going from India 1 to India 2 is not something a lot of consumer tech companies have done successfully (a point made well in this edition of The Nutgraf).

Builders of consumer companies focused on India 2 have to find a large, homogenous audience that is similar in language, demography, demand, location, and serviceability. When all your important axes change every 100 odd kilometers from district to district, this is extremely tough.

Detour 2:

I can take an example from my home state of Kerala. To the casual observer, Kerala is backwaters in Alleppey, and forests in Thekkady.

But Kerala is 560km from top to bottom, almost 17% of the entire Indian territorial landmass. If we use 100km as an approximation, then there are potentially 5 large chunks of different homogenous markets in Kerala.

North Kerala is hilly, with the districts of Kasaragod, Kannur, Kozhikode and Wayanad, sandwiched between the coast and the trailing end of the Western Ghats. There is also a clear Islamic influence in the language and food, with traders from the Gulf finding Kozhikode (or Calicut of Vasco Da Gama fame) as their preferred port of call and expanding northwards.

As you travel south, the landscape changes to become more flat, hilly terrain giving way to coastal plains pockmarked with traditional agriculture, and yes, backwaters. The dialect changes significantly from Kannur to Thrissur (more central) to Trivandrum (all the way South), and so does means of earning income. Kochi is the largest port in Kerala, and hence home to a large spice trade, and also the erstwhile largest Jewish population in India.

If you're building a consumer business for Kerala, you have to figure out the common horizontal across the 560kms from North to South, and then execute to solve for all of these different markets.

Building for India 2 is challenging, but not impossible. FMCG companies have shown best in class execution for the Indian consumer base, working out the largest horizontal point of similarity that they could serve. Other large winners exist, across movies, traditional media, and financial institutions.

But even within these large winners as you go outside the largest common denominator of language - it becomes more challenging to scale. Traditional media for example has large stalwarts in each state - Dainik Bhaskar in the North, Manorama and Matrubhumi in Kerala, Sun in Tamil Nadu, ETV in Andhra/Telangana, but its hard to say there is a large traditional media company that serves the entire diverse Indian market.

So while consumer tech businesses should build for the English language audience first, they also need to have a strong view on how they will go beyond their first large homogenous audience.

What is the next large axes that they can use to find and serve a new consumer market efficiently?

How will the D2C ecosystem scale to a buyer in Meerut?

What should online FD platforms do to reach the retired government employee in Bilaspur who has his PF money in a co-operative bank FD?

And so on and so forth.

Building in reverse

The above thought process leads us to an interesting corollary.

What if companies start from the non obvious go to market? So instead of focusing on the homogenous, India 1 audience, what if they start with the heterogenous audience that is India 2? Are there benefits to this approach? Does this make scaling to the mass user base within India 2 easier?

ShareChat is a good example. The lowest common denominator they built their product around was the 'homogenous' demand for regional language content, and then used language as the atomic unit for product expansion. This is clear from ShareChat's login screen. Asking people to choose their language in 2016 was a big innovation. Language selection put users on the home feed, filled with content in their language, in aesthetics which were familiar to them.

Using this axes of homogeneity - language selection with an AI powered feed - they were able to quickly extend the product across multiple languages and geographies. Splitting the product experience by language has been the mainstay of the app till today.

Lokal is another great example.

Lokal: Building hyperlocal communities for India 2

Like ShareChat used language as the atomic unit, Lokal uses district x town. This means a larger number of atomic units to build, and hence much harder to do (but the good thing about doing the hard thing is that it builds competitive moats).

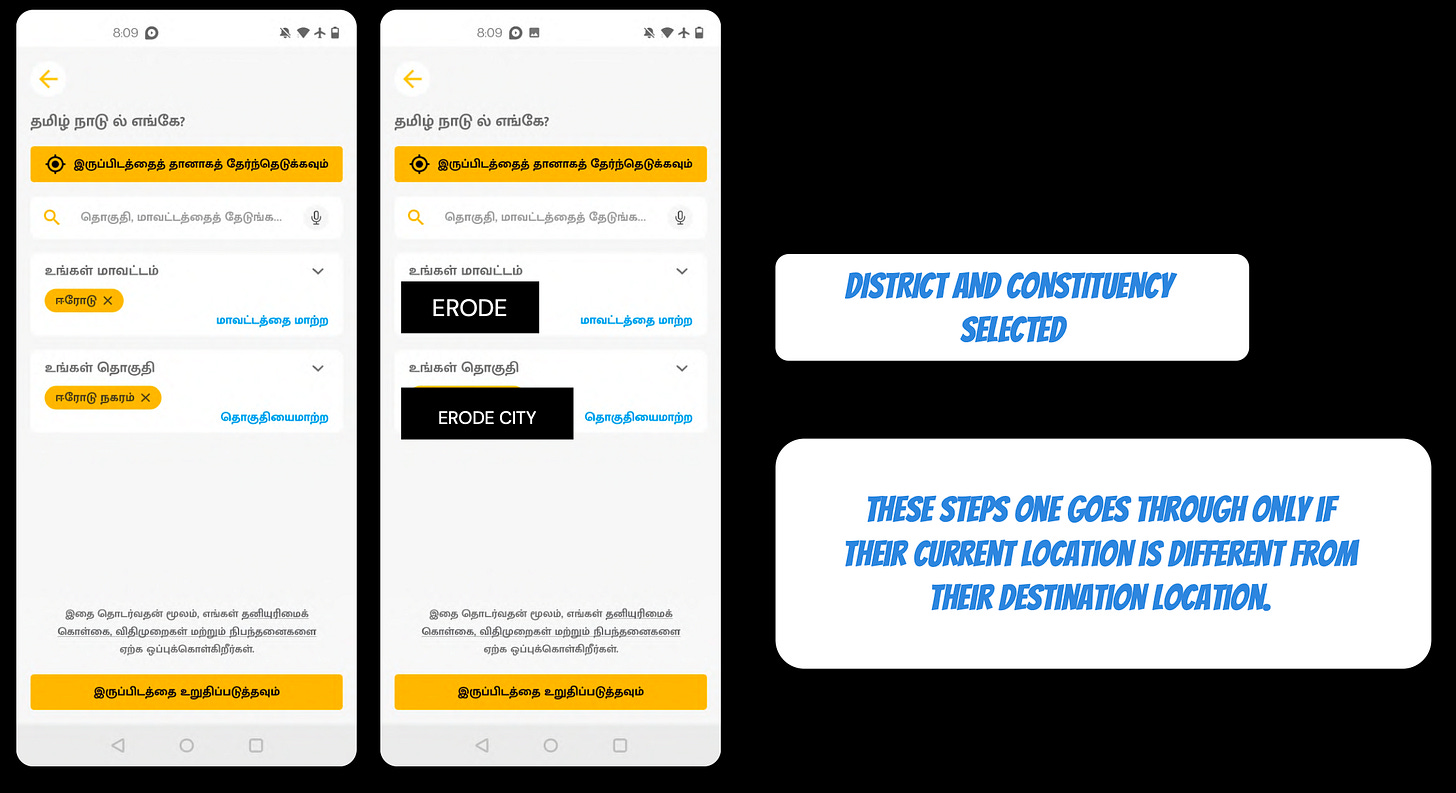

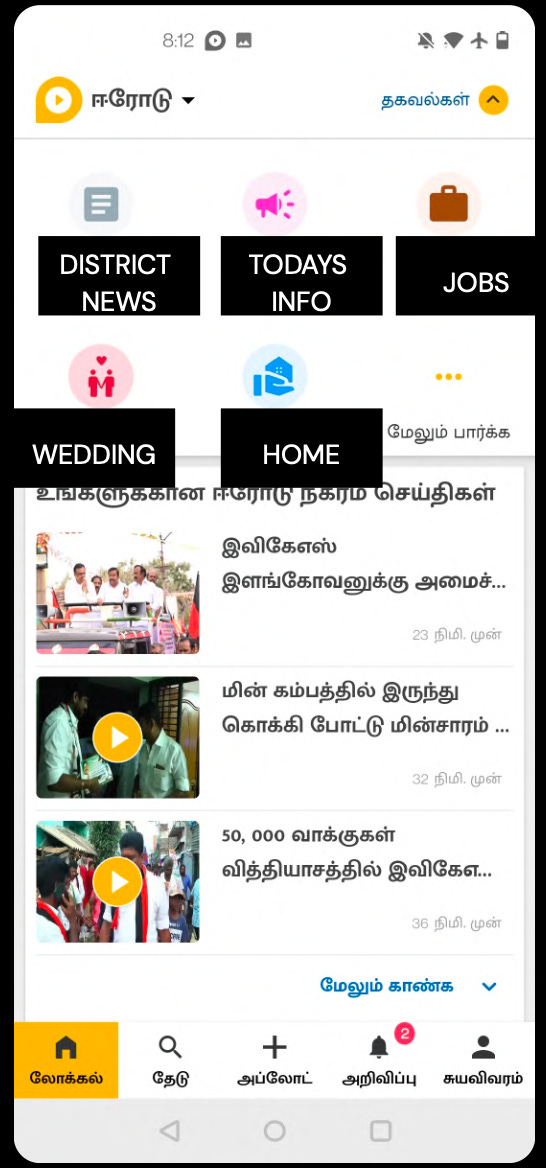

When you sign up, the app asks you to select your location (district and town), and leads you to a feed with updates from around you - news, jobs, matrimony, and ads in the language of that region.

Source: The India Notes Newsletter - Dharmesh Ba

If you've been born and brought up in a city, odds are you won't get the reason for Lokal to exist. What would I gain by knowing that the district health centre is going to be upgraded with an dialysis machine?

But this are the kind of questions that could be the difference between life and death for people in the vast majority of India.

In India 2, life is hyperlocal 📍

Distances make it tough to travel far

If you've been born and brought up in any of India's 600 odd district towns, or more generally outside the top 10-20 large cities, your life would have been dictated by what is available in the 50km radius around you. This is natural. India is a large country, and though the road network is good, anecdotally it still takes an hour to traverse 30 kilometers on the median roads in the country.

Your school would be the local government school, your friends would be from your neighbourhood, your extended family would live close by, you'd buy things from the local kirana, your doctor would be from the village health center and your bank would be a small one room extension of the banks district headquarters in the town center.

And so most of what you need is made available close by

Everything that accounts for 80% of your life's needs is generally available to you close by. This is driven by an ecosystem of local businessmen who have understood their customer deeply over the years and figured out how to deliver the optimum combination of product + service at the right price point. This includes everyone from the kirana shop owner to the person who runs a consumer durables showroom in the village center to the LIC agent who uses his social network to sell policies.

Everything beyond the 80% of needs moves into the ‘wants’ territory. So if you want a good wedding dress, or a consultation from a kidney specialist, or indeed a larger loan, you are headed to the nearest large town - which is mostly the district headquarters.

In that sense, the economy operates like a hub and spoke model, with the districts headquarters being the centre of most of the action. (And now Lokal’s choice of district X town as atomic unit starts making more sense).

Life is driven by trust, and trust is driven by ‘closeness’

'India is a low trust economy' has been the explanation for lots of different product bets (both successes and failures).

This doesn't make sense.

If India was indeed low trust, then

How is your kirana shop owner keeping a running khata for your family's account?

How are the local shamiana (wedding decoration) guys delivering services on 100% credit?

How is your aunt running a local kitty party chitty (often running into a couple of lakhs)?

How is your uncle who deals in cloth sending loads of raw material across the country on the basis of a simple phone call?

If you look closely enough, you'll see that informal credit and money movement is extremely prevalent.

Transacting in money without explicit guarantees is a very good measure of the level of trust in the ecosystem, and based on these anecdotes, ‘low trust’ is not the right narrative.

There is trust, but it is based on a much larger set of principles than what we in India 1 are used to. While we might trust only close family, and need a contract (or bill or invoice) for almost all kinds of transactions, India 2 behaves slightly differently.

Trust here is based on 'closeness' - either through social connections, location (living close to each other), years of doing business with the same people, or other 'multiplayer' aspects.

An axes of ‘closeness’ is social connections. Two examples of these societal mechanics are microfinance, and the (illegal) hawala system.

Grameen Bank, the pioneer of microfinance and lending to the unbanked, is based on the insight that repayments will be driven by social guarantees. These social guarantees are stronger in case of women borrowers. As a borrower you don't want to seem like the person who is not keeping up her side of the bargain in a group setting, especially when people in the group are those you know, and whose opinion you care about.

A less desirable outcome of this trust is the hawala system, which it seems originated in India. Here's Wikipedia

“The unique feature of the system is that no promissory instruments are exchanged between the hawala brokers; the transaction takes place entirely on the honour system. Hawaladar networks are often based on membership in the same family, village, clan or ethnic group, and cheating is punished by effective excommunication and the loss of honour, which lead to severe economic hardship.”

Location is another very important factor in driving closeness, and hence trust. If I know where you live (and have lived since you were born), I can find you quickly. An example of this is that SMBs in smaller cities prefer to hire people who live close by - it is an implicit indicator of trust. Even better, if the person has been living there for a long time - it indicates some physical and societal ties that will keep the employee honest, and not let him pack up and leave quickly.

Sure we don't trust the government (cue corruption) and the bureaucracy, and maybe big corporations, or the media, but when it comes to Subramanian uncle who has been living next to us for 30 years next door, we are likely to jump through hoops.

But then where is this narrative of India being a low trust economy coming from?

In the early days of UPI, you would not be surprised if your friendly neighbourhood kirana owner Goyal uncle was ok giving you credit, but not ok if you said you'd send him the money via UPI. “Beta paisa aayega kaise ayega, kab aayega kuch pata nahi, tum baad mein de dena.” So does Goyal uncle not trust you? No - he didn’t understand UPI, and hence didn’t trust it. And just this morning, he’s just taken Rs 10,000 worth of goods from Ramesh ji on credit, his local distributor who he has been doing business with for years, on the basis of a simple bill of sale.

Let’s extend this.

Imagine that you told new to internet users, who didn't have access to any technology for the majority of their life (remember TVs, washing machines et al only became really mainstream in the late 90s, and the smart phone around 8-10 years ago), that they could download an app on their phone and use it to send money to their family by pressing a few buttons, it would seem unbelievable to them - like magic.

And the thing about magic is that it isn't understandable, and there's a healthy dose of mistrust around a magician’s tricks. ‘are usne kuch to gadbad kia hai’. People don't want you to do magic tricks with their money.

Unless of course the magician is Subramanian uncle.

And here lies the crux of the matter.

India is not a low trust economy. They just don’t trust your product.

And why should they? You haven’t done anything to earn their trust. They don't know you, the only connection you have with them is some screen space on their phone and some mumbo jumbo in the name of ‘user experience’. In most cases your product doesn't even speak their language!

In our little tech bubbles, we haven't figured out how trust works for the median Indian user.

And the challenge is in figuring out how to bridge this trust deficit, and building products and experiences which fit in the users mental model of trust - based on ‘closeness’ - instead of pointing fingers at the audience.

(Yes, the customer is most definitely king).

[Note: Even for UPI, in the end, it was the image of Modi ji plastered across national newspapers along with UPI messaging, and the hard barrier of demonetisation that helped it reach escape velocity.]

I’m aware I digressed a bit (and I did warn you!), but the key point you need to take away is that ‘closeness’ (and more specifically location) drives trust, and trust underpins a lot of my daily transactions. So it is important for me to know what is happening around me.

Politics is all pervasive

15% of India's GDP in 2022 was via government spending. The impact of government spending is more clearly visible outside Indian metros, one of the biggest examples being the MGNREGA (or rural employment guarantee scheme) which pumped in a massive Rs 73000 crore (9b USD) in direct cash into the rural economy in FY ‘23.

Ration shops, government schools, hospitals, government offices, are all indicators of the importance that the government holds in the life of the median Indian. (so much so that the hindi word for government, sarkar is used as a replacement for ‘sir’). As a result, the median Indian is (and has to be) extremely aware of the politics in his locality.

Who is my panchayat member, how do I reach him, and what is the probability of the government getting the road in front of my house getting tarred in the next 6 months? This is all life changing information.

How does this translate to the demand for hyperlocal content?

In India 2 what is happening around me is 10x more important than for city dwelling India 1. My life is controlled by how far I can travel, what I can buy from around me, and how I can use established networks of trust. So I need to know what sale is running in my towns jewellery shop, when the district hospital is open, which MLA is visiting my ward, and which businessman is hiring in his factory.

Regional language Print Media solves for hyperlocal content

The demand for hyperlocal informational content for the India 2 audience today is served by regional language newspapers.

This is expected, and a running theme that comes up repeatedly - if the audience is diverse, the businesses that serve them need to be diverse as well, and these businesses are best built by those who understand the audience deeply.

True to form, traditional businesses have figured out how to fulfil this demand at the scale of an Indian state(s).

Each district gets a different edition of the newspaper, and large towns within the district get specific pages within the print copy.

Like all traditional media, the newspapers make money from advertisements, and very specifically from the long tail of district and town level businesses that today cannot advertise on TV (too expensive) or digital (too complicated). These advertisements can be categorised into commerce (businesses advertising their product or service - buy from a shop close to me), classifieds (jobs - get hired at a place close to where I live, matrimony - get married to someone who is in the same district), government tenders, and obituaries (this is a big deal in India 2).

Over the years, these print media companies have built a formidable brand and product. And it's taken a long time. Dainik Bhaskar was founded in 1958, and Malayala Manorama in 1888(!). Their news bureaus are spread across key towns and district headquarters to source local news, and they have a strong network of journalists - both full time and part time (also called stringers). This coupled with distribution chops has allowed them to build large businesses. Suffice to say they are well entrenched incumbents.

Regional language print media revenue is large and growing

In Kerala, Malayala Manorama's revenue in FY '23 was ~1200 cr, and Matrubhumi earned ~600 cr. Up north, Dainik Bhaskar Groups revenue in FY '23 was ~2300 cr (this also includes their radio channel).

Interestingly, Indian print media has also shown better revenue trends than its global peers. Revenue from advertising in the US print media industry has dropped by 80% in the last 10 odd years, but the Indian print media industry revenue is expected to grow 15% this fiscal and reach its pre Covid trend lines, to around Rs 30,000 crore, which is a very sizeable TAM.

A lot of this growth is driven by regional language newspapers which reach the nooks and crannies of the country, whereas English language newspapers have reached a ceiling in terms of readership and revenue. (Does this theme sound familiar? Hint India 1 and India 2)

Lokal is building the digital version of regional language print media

At a very simplistic level, they are building the digital version of regional language newspapers, explicitly focused on hyperlocal content.

But why digital? What advantages does this give Lokal in its competition with regional print media?

I can think of a few advantages. For one the content is made available in a more real time manner - compared to the 24 hour print media cycles, and this is important for people whose livelihoods are tied tto what is happening around them. On the product side, both content and ad targeting becomes orders of magnitudes better, and engagement is much higher (leading to potentially higher CPMs). There are also distinct cost advantages in sourcing content (no more physical offices, and content can be sourced from UGC creators instead of full time journalists). It is also much easier to innovate and keep up with changing consumer behaviour in a digital only medium.

Are these advantages enough for Lokal to spoil the party of the big guns?

Despite the seemingly stable/growing revenue pool of print media, it is hard to take a long term bet on it. Consumption will become more and more digital as affluence increases and consumer behaviour changes. Digital content has too many native advantages for this not to be true.

And traditional print media knows this - all of them have their own websites and apps. DB group has its own DB Digital arm, with seasoned product and tech professionals recruited to build it out.

This looks like formidable competition from an incumbent. But upstarts like Lokal, have been thinking digital first from Day 1, rather than going from print to digital, and maybe that opens up paths for significant innovation.

What kind of innovation? Two anecdotes.

Anecdote 1: I've talked previously in Monetising Bharat about the long tail of SMB advertisers in India 2. Print media monetises this long tail through a network of agents spread out across the district, who source clients and maintain relationships. What kind of efficiencies (reduce cost / increase revenue) can be enabled by making this process digital? Is it possible to build a completely self serve advertising platform for small town SMBs which allows them to easily (easy = as easy as sharing on WhatsApp) create small budget ads targeted at their local catchment? (FB/Google fail miserably at this - I speak from experience).

Anecdote 2: Here's another potential innovation. Keen observers in Bangalore would have noticed the huge printouts (called flexes) wishing people Happy Birthday that seem to pop up at crowded junctions. Keen observers would also have been confused. What is this about?

This 'wishing happy birthday' behaviour is large and public in India 2. The level of importance (/status) of the person being wished defines the size and location of the flex, and it is placed in locations where everybody in the community can see them, typically in the main thoroughfare of the village (it is these villages that have been eaten up by the urban sprawl of Bangalore).

What happens if this transitions to a digital classified? Can it be monetised more smartly, for example: send a notification to everyone in a 10km radius with my friends wishing me on my birthday? (If I remember correctly Lokal was/is already doing something like this).

Phew, that was quite a ride. Everything from long form to a theory of expanding product in India bottom up, to understanding the demand for hyperlocal, and the potential for apps like Lokal.

In all this its hard to forget that Lokal is up against established businesses, and the way it has built its business (district by district) means scaling is hard, but that could be the key advantage. Each micro market has its own nuance, and each needs to be cracked one by one and then aggregated horizontally. This is slow and hard, but maybe that's the way that the large businesses in India 2 will be built?

Watch this space.

PS: This post intentionally does not talk about specifics on the growth of Lokal - when did it start, how does it think about building product, what are the key challenges etc. This was meant to be a top down view of the hyperlocal content space, and an exploration of the consumer behaviour that is prevalent in median India. A deep dive on the Lokal product itself is for later.

PPS: If you’re here after all this - then thank you and I hope you enjoyed reading!

Profit pools are not deep enough in Tier-2 non-English speaking tech product sales (exception - Real money gaming, softcore content). I am sure you would have seen it twice already - Sharechat and Apna. It is hard to build companies on the hope of perennial investor money.

The premise on trust is not completely correct. The problem with the Indian market is - India is a low trust society. It takes time and money to build trust. Once trust is built, it is hard to move consumers to another brand with the premise of say a better product. Incumbents continue to thrive even with inferior products (but superior trust).

This means - Startups (or upstarts) need a lot more capital (and time) to break into the trust barrier. The shallowness of revenue (and profit) pools in the Indian market do not justify any meaningful return on VC money with these dynamics. A good read would be - Diamonds in the Dust by Saurabh Mukherjea from Marcellus.

I would be surprised if a startup is able to eat into Dainik Bhaskar's market share. If revenue shifts online, it will mostly be the digital versions of the incumbents.

Nicely put. I can relate a lot, I am building in Agritech and came across the trust factor point you mentioned.

I think startups needs to think how they can leverage the existing infra and enabling it through tech.