Emerging Monetization Strategies for Digital Businesses in India 2

I write about 5 emerging themes around monetising India 2 consumers

Note: This post was originally published in collaboration with on their website.

For those of us who are in the business of observing the Indian consumer, Blume’s Indus Valley Report is the starting point. One of the fundamental frameworks the report has used is that of splitting the Indian consumer into three distinct sets - India 1, 2 and 3.

The India 1 consumer set is the top ~120mn consumers in India - who have a majority of the disposable income, behave similar to western audiences, and are almost English native. (I like to say this is the consumer that has rewatched the TV series ‘Friends’ a couple of times).

India 2 is the emerging consumer, with a significantly lower per capita income. Beyond income, they are ‘regional language first’ in that they think in a local language, and that creates a cultural differentiation which shows up in their consumption.

Beyond these is India 3, where free consumption rules the roost.

But, India is a large country, and segmenting 300m people into one homogenous bucket despite their differences in language, location, culture, and ability to pay, leaves a lot of nuance on the table. The image below shows the heterogeneous nature of this consumer.

If we look closely at India 2, we realize that there is a section of this audience which is young, and whose behaviour is driven by aspiration above all else. They are influenced by social media, has some disposable income (and a path to increasing it), and are unafraid to spend.

I call this audience India 2.1, a viable target market for any tech companies who are looking to expand beyond the top ~120mn consumers.

In this write-up, I uncover the key emerging themes around monetizing India 2 and companies charting that path.

But first, some context.

The key narrative around monetising India 2 has always been around their ability to pay, given their per capita income. This narrative is supported by statements like ‘Indians won’t pay for software’, ‘The consumer wants only free stuff’. And even data - Facebook’s ~400m MAU in India drives ~2bn USD in revenue for them, but ~200m MAU in the US drives ~40bn USD.

If we look at things a little differently though, it is possible to see a different narrative.

Historically there have been entities that have been able to monetise India 2 efficiently. FMCG is the pioneer, with their Rs 1/- shampoo sachets setting off a waver that persists to this day. Closer to the tech ecosystem, the Paytm Soundbox is another product that has made 150mn USD in gross subscriptions revenue in the third quarter of FY ‘23. (I’ve written about this before).

So, there is enough evidence that there are large companies that can be built by focusing on India 2, and even existing players who serve India 1 today, will need to look at the India 2 consumer for expansion.

In the rest of this article, we'll talk about some broad themes that are emerging around monetisation, and companies that are charting the path.

It’s easier to build trust with small ticket sizes.

The Indian consumer has no reason to trust your product by default, and small ticket sizes allow them to build trust via trials.

This is not new information, FMCG companies have perfected this with their sachet strategy. New digital product and service revenue models are emerging, buoyed by the adoption of UPI for digital payments and microtransactions.

From the latest version of Blume’s Indus Valley Report.

“Indian startups are also creating a distinct monetisation playbook, by enabling microtransactions, or subscriptions built on top of UPI Autopay, when very few believed that Indian customers would pay or that the only way to monetise was via ads.”

For example, Astrotalk, a platform which allows users to connect with astrologers, utilizes free trials smartly to push users through their funnels. Almost all of their products have a free version.

1/ Free chats which run out after a few messages but still get you a taste of the product.

2/ Live consultations where you can join as a listen only participant.

The person who is talking to the astrologer is kept anonymous (this is a great way for the user to immerse themselves in the product for free)

Once users try the product, paying for consultation becomes easier. Astrotalk offers prices starting from Rs 300 for 30 minutes, making a 30 to 60-minute consultation viable for the average user.

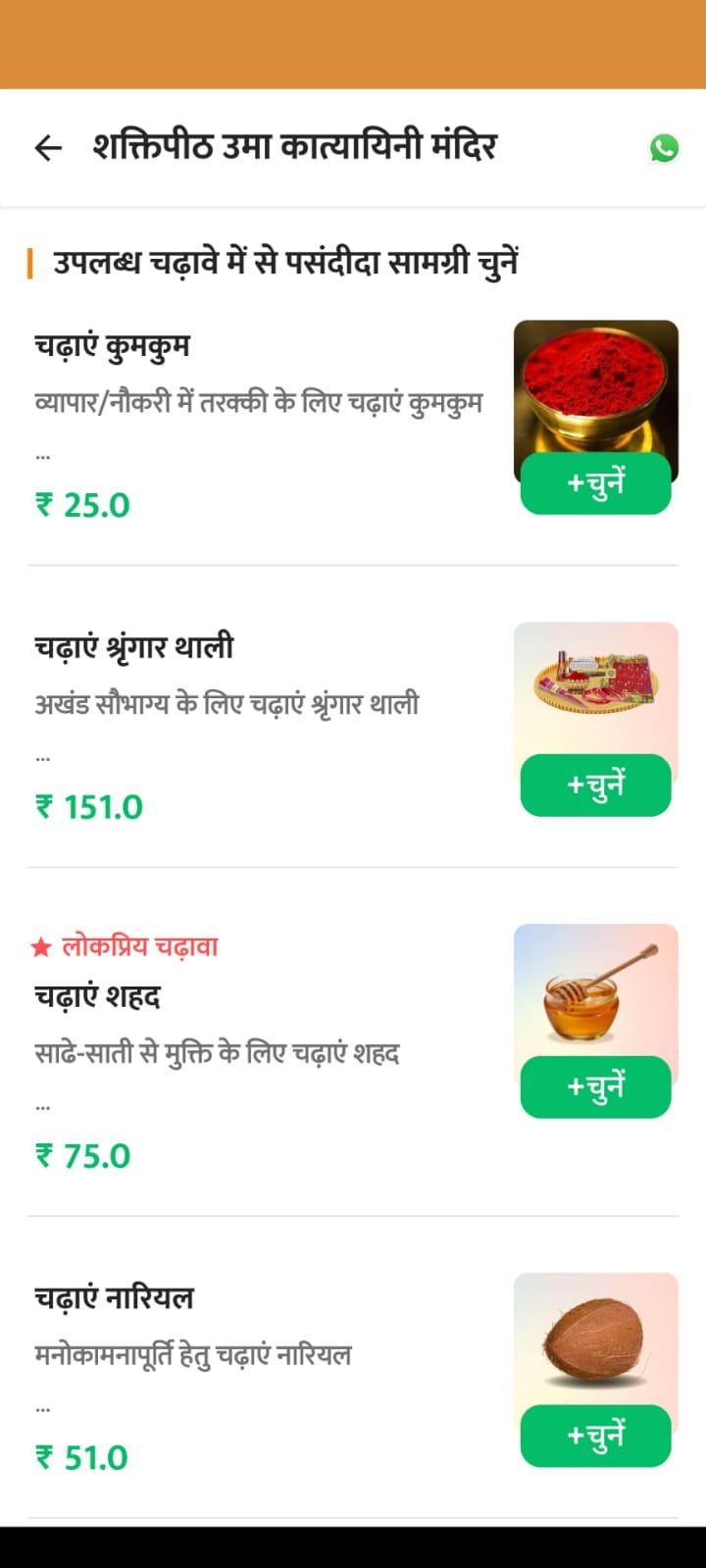

Sri Mandir is another good example. It allows users to conduct online pujas (I’m being simplistic here) across their network of temples. The price points for them start at Rs 25, and a first time user chadhava is available at a discounted price of Rs 1.

Pocket FM is another breakout company, having raised ~100 mn USD in its latest round and boasting an annualised revenue of 160mn USD. Pocket FM is an audio stories app, and has perfected the episodic content + micropayments model in India before transitioning it to the US.

The insight for them was two fold.

1/ Episodic content taps into the mental model of TV series where episodes end on a cliffhanger, and create anticipation for the next episode.

2/ People are willing to pay small amounts to get access to anticipated content, and the coins users buy come in small packages which deliver enough episodes to be valuable.

Consumers will pay if you pack enough perceived value into your offering

It’s probably time to retire the trope of “Indians don’t pay”.

Package the product/service you are offering at the right price point, and pack a lot of value into it. The Indian consumer will pay if he sees a high value/price combination.

From Arindam Paul’s (CBO at Atomberg) Substack

“The Indian consumer( or any consumer with some disposable income) is not price conscious, but value conscious. Show them the value, and they will shell out a premium. But creating, communicating, and delivering value consistently is what makes people pay a premium for brands.

The absolute difference in cost and total cost of ownership is increasingly considered by consumers while making expensive purchases. While someone buying a WagonR will not upgrade to a Mercedes( the absolute amount gap is way too high), people considering a 70k Petrol 2 wheeler will easily upgrade to an EV 2 wheeler keeping the total cost of ownership in mind. Same for consumers moving from 2000 Rs induction fans to 3500 Rs BLDC fans.”

Atomberg is a great example.

BLDC fans have exploded onto the scene over a few years, but Atomberg was not the first to launch BLDCs in India. Superfan.in launched BLDC fans in India in 2012 (Source). Atomberg in contrast launched fans only in 2015. (Source).

However, Atomberg fans definitely looked better (anecdotal). Back in 2019, they were a fashion statement in Bangalore - the value proposition for my friends buying them was that they could be operated by a remote or an app, and they looked good in the home compared to the plain white/off-white fans that middle class Indians were used to. Today, the fact that BLDC is more energy efficient has also seeped into the consumer sentiment, giving consumers more value for the higher price.

Now, having a good-looking, automated, energy-efficient fan at home is a fashion statement, driving Atomberg's growth. Atomberg has grown 10x in the last four years, from ₹69 crore topline in FY20 to nearly ₹650 crore in FY23." (Source)

As the Indian consumer becomes more aspirational, she is going to look for products that are more than just ‘functional’.

India 2.1 is looking for an offline premium experience because they haven't experienced it yet

The dominant trend in consumer spend is premiumisation. This is evident across a lot of categories - apparel, food, beauty, and electronics.

“More than 70% of the new products launched by India’s largest consumer goods maker Hindustan Unilever in the last two years were in the premium segment.” (Source: ET)

Here’s how I look at it - The Indian consumer is now aspirational, across India 1 and India 2.1. India 1 has had access to the ‘experience’ of shopping like going to malls and upscale retail outlets for some time now, and now ‘Going to the mall’ is a commodity. India 1 consumers are now trading off this ‘experience’ for convenience, which explains the growth of e-commerce and D2C brands in India 1 providing search + convenience.

But this isn’t how things are panning out for the India 2 consumer.

For this audience, shopping has never been available as an ‘experience’ until now. Access to social media fuels aspiration, and an increasing disposable income means that consumers are willing to spend on goods and services they wouldn’t have before. For them it’s not just about the convenience of accessing the product, it's also about the shopping experience as a whole.

While India 1 goes the D2C route (trading off experience for convenience), India 2.1 is going the offline (trading into the shopping experience), especially across retail and F&B.

Air conditioned retail spaces, large aisles, good lighting, product choices - taken for granted by India 1, are novel for India 2, and shopping is almost like a family outing rather than a chore. This is visible in the increasing investment in malls in Tier 2 and 3 towns, and more generally, in modern retail.

We know about the D-mart success story, and I recently wrote about ‘SuperK’, an innovative business which is transforming kirana stores into modern retail outlets to keep up with what the consumer wants.

Another story which has taken the business world by storm is Zudio, the India 2 cousin of Zara - a premium-like shopping experience at an affordable price point (I’ve referred to ‘faux-premiumisation’ in a previous post’.

Here’s a screengrab video of a Zudio store in Ranchi at 9pm - stock is out! If you visit a ‘modern’ store in a Tier 2 town, you’re likely to find it packed to the brim.

By all accounts, Zudio has been the major reason for Trent’s success (owned by Tata Group, which also owns Westside) over the last few years. Zudio’s store count has grown to ~350 and it contributes ~48% of Trent’s revenue in FY ‘23 (from ~2% in 2018).

A quick sidebar into why Zudio works - Affordable trendy fashion, packaged in a premium shopping experience

Aspirational customer - Thanks to social media, the India 2.1 consumer is much more aware of what is ‘trendy’ in fashion and apparel.

Price - Trent’s other chain, Westside, failed to make an impact with this audience because of it’s premium positioning, both on brand and price.

Shopping Experience - Having innovated on both trends and price, Zudio delivered the final blow - a shopping experience in a modern retail format that made shopping something beyond a transaction. Consumers could now buy, and feel like it was an outing as well.

Build for the different online behaviour of India 2

An app that has been gaining traction is ‘Crafto’ by Kutumb. The app allows users to create custom quotes for sharing on WhatsApp.

The sharing of ‘Good Morning’ messages on WhatsApp is not new. It was this behaviour that ShareChat tapped into to generate organic installs on WhatsApp. Users logged on to ShareChat to find the right messages that they wanted to share with their friends and family on WhatsApp, along with a link to download ShareChat.

Crafto has tapped into the nuance of users wanting their names and photos with these images - a touch of personalization (remember 123greetings.com?). Crafto allows you to add your name and photo for a fee.

This is a great combination of identifying sharp user behaviour for this audience, creating an app does only one thing, and monetising it via microtransactions. Even the app title on Play Store is optimised for organic traffic ‘Crafto - Daily Morning Quotes’.

Unlike India 1, India 2 is not digitally native. Their first interaction with the internet was through mobile devices, with the dominant apps being WhatsApp, YouTube, and Facebook. As a result, there are differences in how the audience thinks about online behavior.

For example, one dominant behaviour is ‘browse’ not ‘search’ - access to information is via browsing feeds - on WhatsApp groups, YouTube, Facebook and other content apps. This is very different from how you or I started with access to the internet, using Google Search as the primary entry point.

For this user, apps are also a very important concept. A lot of ‘searches’ originate directly on the app store for specific needs, and the mental model is ‘what app can I use to do that’.

All of these differences in behaviors present opportunities for folks looking to build in India 2.

However there are some cautionary tales. Experiments in live commerce (translating browse behaviour directly to buy) have been unsuccessful so far, unlike TikTok in China, where live commerce is a large industry. Translating behaviours from China (which is considered to be a very similar market to India) might not generalize across all verticals.

Start with monetising the younger audience

I use the concept of the ‘pioneer user’ to devise GTM strategies for an India 2 audience. Source

I saw the panwadi (pan shop owner) next to our office using ShareChat and started chatting with him.

He had left his village in Bihar at a young age and started his trade here, and now owned a few pan stalls. He was now the bridge between his village and Bangalore, getting young people from there to the city and setting them up here (giving them initial accommodation, connecting them with business owners, lending moral support). He was close to the trends in a big city (tech or otherwise), and had learnt how to use apps we take for granted (eg: UPI) to get ahead in life. Because of this he was a pioneer in his community in using digital products across payments, e-commerce and social media.

For example, he acted as the trust bridge for bringing UPI payments into his village ('paisa bhejne ke lie yeh nila button dabao' 'kuch gadbad hogi to mujhe batana'). For us a failed transaction might be relatively trivial (we reach out to customer support, use twitter, maybe even ping the PM of the app), but the risk of even a small amount of money not being exactly where it is intended is almost existential for a large % of the Indian audience. A user will not touch a button in a 'paise bhejne waala app' he is absolutely sure what it does - and this is where personal support helps.”

Pioneer users are your early adopters, and a marketing strategy that reaches the pioneer users is likely to give products an early advantage. Meesho started by targeting women sitting at home to push their reseller model, and tapped into existing behavioural and cultural nuances (women aren’t allowed to work full time jobs easily). These initial users drove sales and word of mouth to grow demand for Meesho products.

More generally, younger people are an archetype of pioneer users. They are the most savvy with the internet and digital payments, know how to find and research the product, are ok to try new things, and use social media to spread the word if they like what you sell. Digital products like ShareChat’s audio rooms, Eloelo (live video rooms), and even Astrotalk (to a certain extent) have reached and monetised a younger audience base.

Monetise earlier vs later

Irrespective of whether you're raising venture capital, it makes sense to test out monetisation as early as possible. With the prevalent macro conditions, and the (sometimes dreary) narrative around this audience's paying capacity, building conviction on monetisation earlier rather than later is the best possible approach. The best case is you make money on Day 1.

A good example is the real money gaming world, where the business model is geared to monetizing acquired users quickly. Astrotalk has built a successful model by deeply optimizing their acquisition and product funnels to be unit economics positive on each user. Both models use revenue as a lever for retention rather than the other way around.

Companies that delay monetization or unit economics have struggled to prove the scale of monetization for their valuations to hold true.

Conclusion: Monetising is hard, not impossible, and there are tailwinds of consumers aspiration

There is enough evidence of profit pools to be created by selling to India 2. However, expecting the growth mechanics that worked for India 1 to work in India 2 in terms of go-to-market strategies, products, and business models is unfair. Building for India 2 is like building for ten different countries, each with its own language and cultural nuances. This unique challenge requires new models to be tried, discarded, and tried again; new behaviors will have to be built, and big bets will have to be taken. The ecosystem should prepare for this.

Until next time!

Really insightful read, Mithun! Always enjoy your articles—they're like the croissant to my coffee, to be savoured slowly, and like the aftertaste, the insights linger in your brain for a long time afterwards!

Hello Mithun,

I hope this communique finds you in a moment of stillness.

Have huge respect for your work, specially the unique reflections.

We’ve just opened the first door of something we’ve been quietly crafting for years—

A work not meant for markets, but for reflection and memory.

Not designed to perform, but to endure.

It’s called The Silent Treasury.

A place where judgment is kept like firewood: dry, sacred, and meant for long winters.

Where trust, patience, and self-stewardship are treated as capital—more rare, perhaps, than liquidity itself.

This first piece speaks to a quiet truth we’ve long sat with:

Why many modern PE, VC, Hedge, Alt funds, SPAC, and rollups fracture before they truly root.

And what it means to build something meant to be left, not merely exited.

It’s not short. Or viral. But it’s built to last.

And if it speaks to something you’ve always known but rarely seen expressed,

then perhaps this work belongs in your world.

The publication link is enclosed, should you wish to experience it.

https://helloin.substack.com/p/built-to-be-left?r=5i8pez

Warmly,

The Silent Treasury

A vault where wisdom echoes in stillness, and eternity breathes.