The India Story: Migration & Macroeconomics

What narratives about the economy emerge from emigration patterns and car sales?

Hello to all the new folks who have signed up to the Indian Pivot over the past month or so! I've been way behind my posting schedule - mostly due to a combination of travel (split between the post monsoon humidity of northern Kerala and the wonderfully cool fall climate of Istanbul) and a mild case of (inevitable) writers block. So I've dusted off a few notes from my drafts, and put that together in a meandering post (and yes, this post will meander. I'm a big fan of random walks - they have helped me to figure out non-obvious patterns, and hopefully these narratives will help you too.)

Here we go.

In a previous version of this newsletter, I talked about segmenting India 2 users by their level of aspiration, and how this aspiration is manifesting in new consumer behaviours like 'faux premiumisation'. I also hypothesised that aspiration more strongly in a younger population, and that India's famed demographic dividend should provide enough tailwinds for businesses trying to serve this young aspirational population.

But there was something I missed.

The Great Indian Migration

2 years ago, I met a young 23 year old in Kerala. Like most Gen Z youth in Kerala, he had completed an engineering degree from a Tier 4 college, done an MBA from another Tier 4 college, and had (predictably) found no jobs after that. After short stints at a couple of companies as a sales rep, he approached an educational consultancy which got him into a Tier 3 college in the UK, for a run of the mill masters, and he shipped off, mortgaging his parents house in the process.

To a large degree, this mimics what has happened in Kerala over the last few decades. Despite being a standout performer in human development indices, the state has struggled to provide jobs to its highly educated and aspirational work force. Given its age old trade ties, Malayalis emigrated in droves to the oil rich shores of the Gulf (United Arab Emirates, Qatar, Bahrain, Kuwait, and Saudi Arabia). According to this article, at any point in time Gulf countries provided employment to 10% of Kerala's working population. This has undoubtedly led to large amounts of prosperity for the state, evidenced by inward remittances to the tune of 1 lakh crore in 2010, leading to a boom in real estate, construction, hospitality, retail, education and what not (go to any small town in Kerala and you'll be able to spot a 'Dubai' mall). This is how it has always been in Kerala, but today you’d expect that with 'India being a beacon of growth’, such stories of emigration would be anecdotal at best.

2 years later, on 29th July 2023, 7000 odd youngsters crowded into the Rajiv Gandhi indoor stadium in Kochi for a unique record attempt.

"The record for largest pre-departure briefing given to students was set by Santamonica Study Abroad Pvt. Ltd. of Kochi, Kerala. A total of 7236 Visa-received students for Canada assembled at the Rajiv Gandhi Sports Centre (Rajiv Gandhi Indoor Stadium), Kochi to receive pre-departure briefing about the culture and traditions of the country they will be visiting." Link

Let that sink in for a minute. 7000+ students, from one state, to one country, only for the fall intake.

If you think this is only a Malayali phenomenon, hold that thought.

Indian students going abroad for higher education recorded a six-year high in 2022 at 750,365, according to the education ministry data submitted in Parliament on Monday. The number of students going overseas has increased by a significant 68% in comparison to 444,553 students going abroad in 2021.

But what prospects await them? A vast majority of these students are going for non-STEM degrees in Tier 2-3 colleges, from smaller cities in India. Needless to say, things aren't very rosy. Canada takes 40% of outbound student intake from India in 2022, and a recent news report highlighted a host of problems, starting from a lack of housing and part time jobs, exorbitant fees from private colleges, and much else besides.

“Some students are living in cars, while others are forced into expensive motels that can cost up to $100 per day. This financial strain adds to the existing challenges of adjusting to a new culture and educational system,” Khushpreet Singh, a student from India, was quoted by BayToday, a local North Bay news portal. Read more here.

Despite all this, outbound student flow seems only set to increase. How badly have we failed our aspirational youth? What is the narrative of GDP growth masking?

Outside the prosperity bubble

There are many threads to be pulled at here, each of which is a dismal reality check on the macro level narrative.

The India story is centred around a growing GDP and a young and educated workforce - a combination of this theoretically puts us on a path to becoming a higher middle income economy in the next 5 to 10 years.

But if you look outside the bubble, and talk to the median 25 year old in India, the old spectre of education and jobs still haunts our youngsters. Our 'excellent' higher education system is such that an average degree in India doesn't even guarantee you an average job - creating legions of organised job aspiring youngsters with useless degrees. On the other hand, increasing access to information has fuelled aspiration like never before.

Aspiration with no means to satisfy it, has led to the migration that we see in the short term. In the bull case, things turn out like Kerala, with large inward remittances from workers employed abroad in a few years time (but you have to understand the macro scenario today is not really in favour of western economies, unlike the Gulf a few decades ago which was in the middle of the oil boom). The bear case is lost foreign exchange, shattered dreams, and a missing Indian middle class, which has uneasy ramifications for the economy over the long term.

What are some other offshoots of this narrative?

One is a boom for companies who are enabling this emigration of our younger population - all the way from SMBs like Santa Monica in Kochi (referred above), to startups like Leverage Edu and Leap Scholar, to banks and NBFCs who want a piece of the education loan pie.

The other is government jobs - as the median aspirational youngster is squeezed out of the private sector because of an unusable degree, the lure of a steady job in the government will become larger, despite all the associated challenges of lack of supply. 'Government job prep' as a theme is likely to get bigger in edtech.

The third is tough, but the only real solution (and I'm acutely aware of the enormity of what is required) - a revamp of our education system to focus more on vocational education, leading to more income earning jobs, rather than dead end degrees. As a corollary, there are opportunities in up skilling for entry level jobs (for example Virohan trains people in the paramedical field).

The lack of 'good enough' jobs (the unemployment rate in India is ~8% today, up from ~5% fifteen years ago) is leading to an increasing trend of migration for our aspirational youth, for whom what the country offers is just not good enough. This is an obvious indicator of structural issues in our economy today, and this got me thinking - what do broader economic indicators say, and how should we read top level indicators along with bottom up observations like these? This leads to our next section, where I talk through two different narratives on growth, and the choices those narratives put in front of entrepreneurs.

It’s all about growth - but growth of what kind?

India's per capita income is projected to improve from ~2500 to ~5000 USD by 2030, and an important question to answer is how this growth will be distributed.

There are two narratives here.

The first one is the happy narrative - growth is driven by manufacturing which moves a large % of our population from agriculture to more organised industry, and the corresponding income benefits are distributed more evenly across the population.

The second is the 'unhappy narrative' - where economic growth is concentrated towards a smaller % of the population. This does seem to be what has happened over the last 3 years, especially post Covid.

Some macro data points to a K shaped recovery - which means the rich are getting richer

While at an average level, the economy seems to be doing well (evidenced by GDP growth at ~8%), these averages mask some of the realities which are otherwise becoming evident.

Domestic two wheeler sales are at a 9 year low, and sales of entry level cars continue to decline

This is an indicator which looks at the economic health of the middle income groups in India. This makes sense - two wheelers are one of the first large purchases that a lower income family makes one it reaches a certain economic level). Domestic two wheeler sales have dropped from ~20mn in 2018-19 to ~16mn in 2022-23. This is a 9 year low.

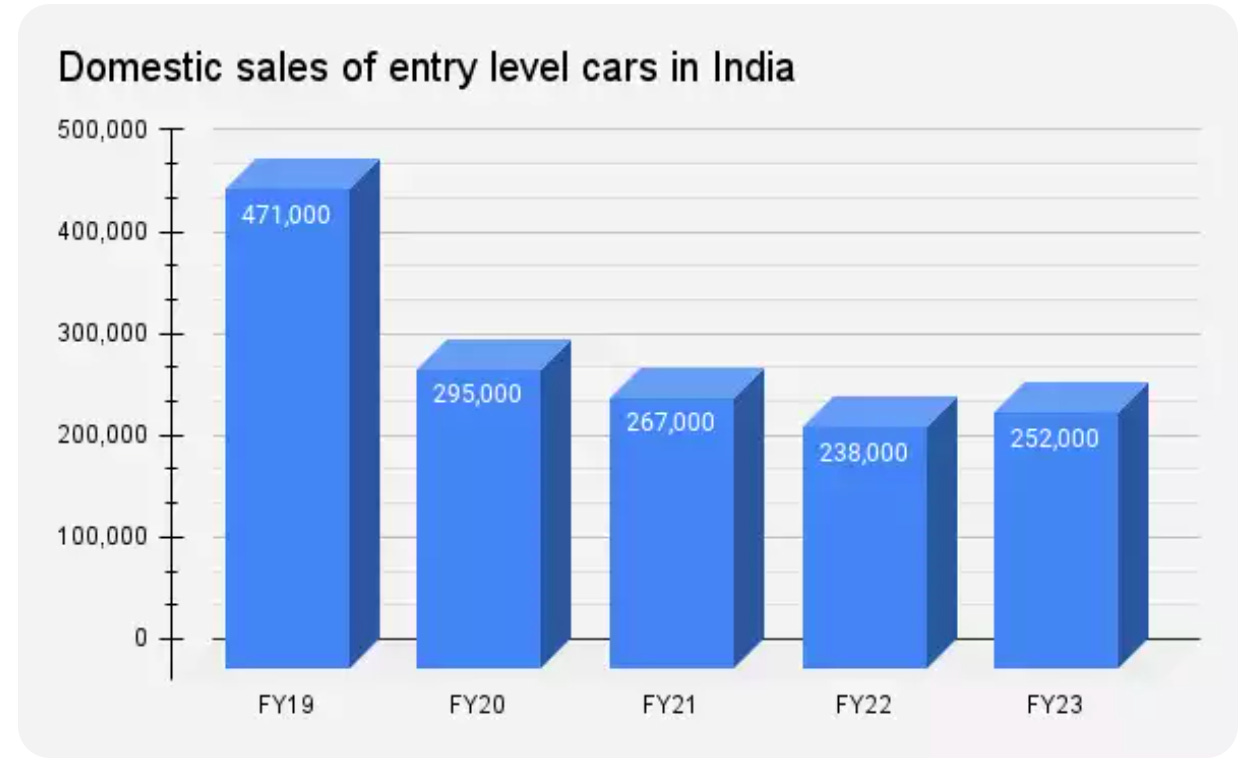

Of course, you could argue that consumers have graduated to buying lower end passenger vehicles (perhaps substituting their Pulsar for an Alto), but sales of entry level cars continue to decline. In 2018-19, sales of mini and compact cars stood at ~2mn. It has fallen to ~1.4 million in 2021-22. (Source). Strangely, latest numbers show that passenger vehicle sales are set to do their best year ever in FY 23, but this is driven completely by a massive increase in the sales of SUVs.

Compared to 2016-17, when the sales in this segment stood at 5.83 lakh units, the mini car sales have dropped 57% to clock 2.52 lakh unit sales. Maruti, which has been a leader in small car sales, stopped the production of Alto 800 hatchback this year.

On the other hand, demand for SUVs and luxury cars is off the charts.

From this article in the Economic Times: “SUV sales are projected to be around 1.9 million units this year, a multi-fold increase from 363,000 units 10 years ago in FY14. The share of hatchbacks and sedans in the sales mix fell to 40% from 71% in the past one decade”. Almost every second car sold in India today is a utility vehicle (SUV/MPV) - sales of these cars have continued to climb because of resilient incomes and lower sensitivity to price increases among affluent buyers.

Luxury car sales seem to follow the same trend. From the Deccan Herald:

“2022 saw the around 37,000-38,000 luxury vehicles sold, an increase of 50 per cent from 2021. In comparison, sales in the mainstream car market only grew 23% in 2022.”

High end apartments are flying off the shelves

From The Ken.

“Sales of apartments priced over Rs 1.5 crore (US$181,300) doubled in 2022 in India. Luxury projects priced above Rs 2.5 crore (US$302,000) in tier-1 cities are getting sold out at the pre-launch stage. Inventory overhang for such projects is at a decadal low,” said a senior employee at JLL India, a real-estate services company. They did not want to be named as they were not authorised to speak with the media, and the data is not public.

And here’s some data from tax returns

The number of individual taxpayers earning more than `1 crore jumped from 1,11,939 in preCovid 2019-20 to 1,69,890 in 2022-23, a 51% upswing, according to data periodically released by the Central Board of Direct Taxes (CBDT). This defies conventional wisdom and bolsters the narrative of a K-shaped recovery that says the rich were getting richer. In the last three financial years, India added 57,951 new crorepati taxpayers, a significant number considering the erosion of output and loss of jobs amid the gloom and doom of Covid-19.

Aside: What is a K-shaped recovery?

A reading of these numbers seems to suggest that the growth in our economy in the recent past has been extremely lopsided. While readers of this newsletter are probably beneficiaries of this shape of growth, from the perspective of the economy in the long term, this is not ideal.

Why? According to the OECD.

A certain degree of income and wealth inequality is a characteristic of market economies, which are based on trust, property rights, enterprise and the rule of law. The notion that one can enjoy the benefits from one’s own efforts has always been a powerful incentive to invest in human capital, new ideas and new products, as well as to undertake risky commercial ventures. But beyond a certain point, and not least during an economic crisis, growing income inequalities can undermine the foundations of market economies. They can eventually lead to inequalities of opportunity. This smothers social mobility, and weakens incentives to invest in knowledge. The result is a misallocation of skills, and even waste through more unemployment, ultimately undermining efficiency and growth potential.

Ok, so that’s a quick run down of the data, and what seems to be happening at a macro level.

But as an entrepreneur, why is thinking through these narratives important? As someone who wants to build a business serving the diverse Indian customer, it's crucial to understand the macro data which govern the economic fundamentals (roti, kapda, makaan) of consumers and households.

I say 'understand' and not 'act', because data is only one of the axes that can be used to understand the potential consumer. In fact, the best businesses and founders are in some sense ahead of data because they are able to look into the future to extrapolate macro trends from anecdotal user behaviour, much before these trends become evident in data. They are ahead of their time, and in the most elite cases, are able to create trends, markets, and businesses where none previously existed.

If you were a founder today, which of the two trends would you bet on? The unhappy path means there is going to be a concentration of wealth in the hands of a few. What would you build - fundamentally low volume high margin businesses? Luxury D2C? Private clubs? Gourmet food and high end travel? Sneaker re-selling?

Or are you the more optimistic kind? (I'm in this category, because, you know, never bet against human potential and all that). I am aware that a lot of the data I presented above might seem like cherry picking to drive a negative narrative, but the intention is only to drive visibility of things that get lost in hype cycle narratives. When you’re starting to build for a large consumer market and committing years of your life to it, it is important to understand the context in which your customer operates. I, personally, am bullish on the Indian consumer story, and believe that India 2 is where the next set of large consumer opportunities lie.

Aside: A relevant question to ask of course is where this consumption growth is going to come from if there are no jobs to generate income? In the short term, I think this is going to be driven by a draw down of savings from the previous generation coupled with an explosion of consumer credit. More on this in a later post.

Until next time.

Some Housekeeping

If you’ve meandered this far, thank you, and I hope you have learnt something from this. Please share this post with those you think would love to read it.

If you’re a founder looking for advice on your product, GTM, hiring and more, I’m happy to help. Please reach me at myth.12887 [at] gmail.com

Here are the working titles of some drafts I have in progress, which will find their way into your inbox soon.

Large consumer trends for India - Commerce, Credit, and Social Gaming

India as a status driven society - Trends and Opportunities

The Creator Economy in the age of Generative AI

Thanks for the insights here! I wonder if part of the reason the sales of compact and mini cars have dropped in recent years is because the standard compact SUV has become cheaper and more widely available. I agree with your theory on future demand in India being driven through savings and an increasing reliance on credit. I think cumulative money in Savings account is at a decade low right now. I personally think it's a good thing for the economy. We need more money to go around to keep growing.

Thanks for the post