Risk hai to Ishq Hai: High Risk Games in India 2

How a combination of socio economic factors has upped the risk quotient for India's youth

To all my regular readers (which I hope there are many of) - apologies. This edition is super delayed owing to some planned travel and work. I hope this particular thought stream (sort of) makes up for it.

To everyone who has subscribed, I’m now picking up part time assignments working with founders set up their product strategy and execution stack. Here are some more details. Hit me up if you think I can help!

The great thing about sabbaticals is that they allow you to get bored. There’s only so many content you can fill your day with, and as a matter of course you will find yourself nursing that black coffee, soaking in the winter sun, and asking the Swiggy delivery executive who turned up with the 3rd order of the day if he trades in options.

Or maybe that’s just me.

Some such conversations threw up a lot of interesting questions.

Why does the median Indian gravitate towards high risk, low probability paths to success? How do thousands of youngsters bet the best years of their life in pursuit of a handful of government jobs? How did this mindset influence the spectacular rise and fall of crypto trading in India? What does this frame of reference tell us about the sharp rise in day traders on the stock market?

Through the next few paragraphs, I will make the case that the unique circumstances of India’s young consumer base is driving (and will continue to drive) a variety of risky behaviour.

How are India 2’s youth thinking about their future?

It’s election year. Predictably, there is a lot of noise about GDP growth (projected to double by 2030), UPI payments, tax collections and assorted metrics which tells us that on average, things do look better for the India. And it is also easy (and potentially right) to argue that in the medium to long term, India’s economic prospects look bright, and hence the median Indian will have a better life than today.

But, in the long run, we are also dead.

So it’s also important for us to ask what is happening in the here and now, and a good indicator is what India’s just-graduating-first-job youth thinks about his prospects.

Let’s start with the macro indicators - Unemployment rate is trending at double digits since late last year, and experts say a rate between 7 and 8% is the new normal.

Unemployment is particularly pronounced in the rural sector, where it has actually risen faster than urban areas.

So clearly there is a lack of jobs. But India being India, there are a lot of unique factors which add another layer of pessimism to anyone thinking about upward mobility economically and socially.

India is lawless: Compared to the average Western country, we do terribly on justice.

Realistically, the average Indian will never get justice - hence the reluctance to engage in court-kacheri ka chakkar. This means those who interpret the law/rules (all the way from your average government clerk to the celebrated IAS officer) has way too much power. His word is law - because you can’t expect to go to courts and get them to do anything. This leads to corruption, lack of faith in contracts, and a general sense of inefficiency.

Social inequalities driven by birth lead to economic inequalities: Sometimes in unexpected ways. One example is India’s female labour force participation - the lowest among G20 countries (23% vs the global average of ~50%).

A potential reason is the caste system.

An estimated 100 million Indian Hindu women are disallowed from working. Constraints on Hindu women’s work are tied to the practice of female seclusion required by caste norms, the set of religious and social laws that governs behavior within the Hindu caste system (Chen, 1995; Field et al., 2010; Luke and Munshi, 2011; Jayachandran, 2015).

The Economics of Caste Norms: Purity, Status, and Women’s Work in India

So now if you’re a 20 something in India 2 with an average college degree, you’re in a town where there’s no private sector jobs. If you start something of your own you have to deal with corruption and bureaucracy, and the entrenched social realities pull you down.

It’s hard.

Contrast this with the stories coming out of the developed world. Despite all its faults, the one thing everybody will agree with about the US (and maybe more generally, the West) is that the probability of success for the same amount of input (aka hard work) is much higher. (Hence the great American Dream.)

And this shows up in data.

And if you spend time in rural areas, signs of the Indian youth’s versions of ‘quiet quitting’ are very visible.

But it is not just the labour class that desires to travel to Israel for work. Young, educated Indians are also applying for these jobs in their search for a stable income.

Sachin, a 25-year-old final-year engineering student at a state-run university in Haryana, also appeared for the interview. “Nobody would want to go to a place where rockets fly overhead but there are little opportunities in India,” he told Al Jazeera.

Of the 96,917 Indians, 30,010 were caught at the Canada border and 41,770 at the frontier with Mexico. The rest are those tracked down mainly after sneaking in. The total marks a fivefold increase over 19,883 Indians caught in 2019-20.

I've written previously about the migration trend from Kerala, to universities abroad, despite the limited opportunities that are available post graduation from a no-name college in the UK/Canada.

What we see here is young India 2 voting with their feet - they do not share the optimism of policy makers, business leaders and India 1 around the short term prospects of the economy, and more specifically, jobs.

For them, things have not changed materially, and the internet and social media telling them they are being left behind. They are trying to find their own paths to make money.

A lot of the current answers on how to do this seem to be around migration - from rural to urban, from north and east to south and west, and more concerningly from India to the world.

Aside: While writing this, I have the classic Malayalam movie Naadodikaattu released in 1987 (36 years ago), running in the background. Set in rural Kerala, the plot revolves around 2 young men with B. Com degrees who are working as peons in a private company. Frustrated with their circumstances, they take a bank loan to, somewhat optimistically, start a dairy farm, and are conned by the person who sells them cows. With no way to repay the loan, they plan to take a boat which will deposit them illegally on the sandy beaches of the Gulf. Before leaving on this journey, the lead protagonist (played by Mohanlal) visits his mother, and tells her - ‘There are no opportunities here, and no way to improve my condition. The only way is to take a long and risky journey - I need to escape this place’.

The more things change, the more they remain the same.

But what about those who can’t afford to migrate, or prefer staying in India because of whatever reason?

For them it’s - Risk hai to Ishq hai.

The Government Job aka Sarkaari Naukri

12th Fail, TVF Aspirants, and Sandeep Bhaiya are the most recent in a clutch of popular media which romanticises the UPSC dream. To be fair, the dream did not really need any romanticisation.

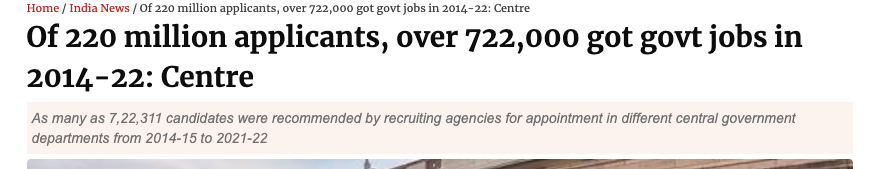

There has been a persistent, large gap between the number of applicants and the number that get any sort of reasonable government jobs. The acceptance rate is ~0.3%. This is the definition of high risk - low probability of outcome.

With the context above, it should now be easy to understand why millions of youth still undertake the sometimes years long pilgrimage to prepare for a government job. There simply is no other option - no private sector jobs, low returns from agriculture, and if you do want to take the risk of doing something on your own, you have to contend with a social and governmental system that does not reward individual enterprise. You succeed despite them, not because of them.

So obviously there is infinite demand for test prep - specifically for government exams. It’s estimated to be a 30bn dollar industry, dominated by legacy players, with tech first companies like Unacademy using online as a beach-head and now trying to build a sustainable business.

There are a few more interesting examples on this theme. Entri.app aims to crack this market starting with a vernacular focus (each state has its own version of exams to crack different government jobs at the state level). Most recently it raised 7m USD in a Series A led by Omidyar Network.

It’s clear that the market is large - and this is both a challenge and an opportunity. It’s an opportunity because whatever way you attempt to approach the problem, you are likely to see some initial success, but it will very quickly become challenging to figure out how to scale this business given the competition, and the fact that demand at scale really exists only in offline businesses. Many founders have struggled to navigate this gap from initial success to eventual scale.

Crypto and Bust

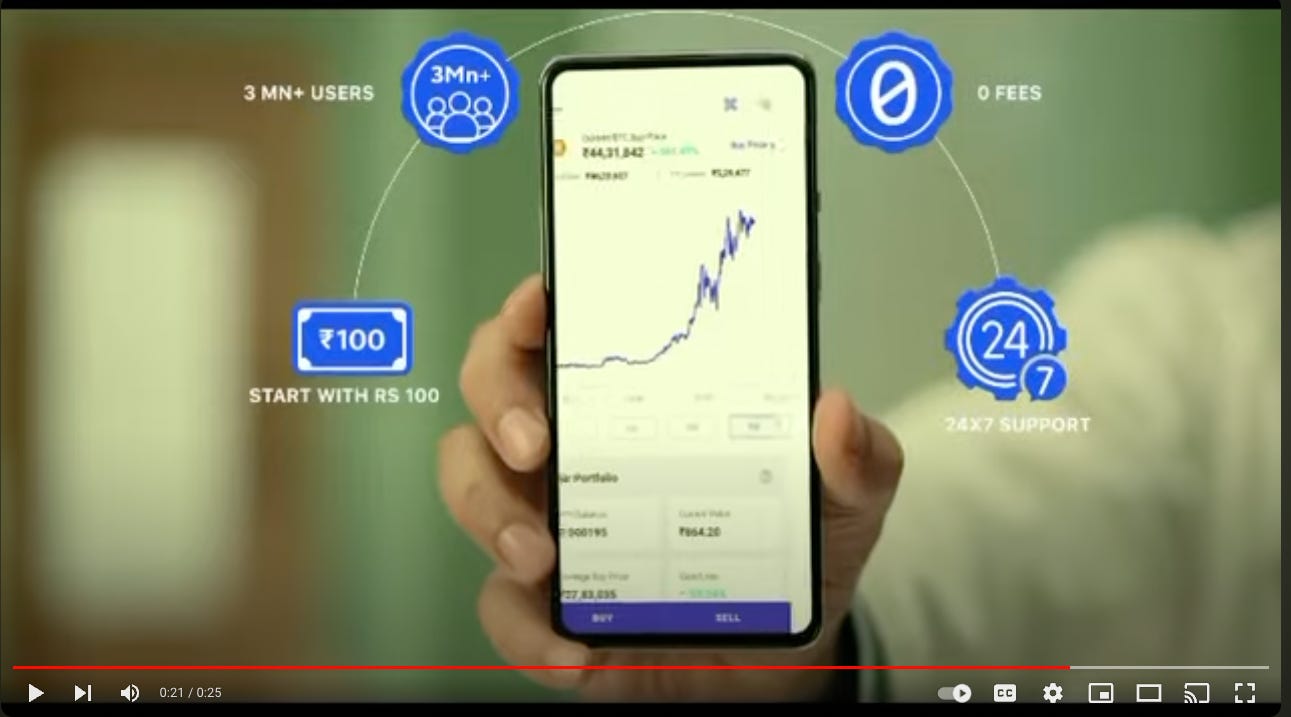

The evolution of Coinswitch’s ads from the middle of 2021 to the end of 2021 tells us a lot about which direction the market was pulling one India’s largest crypto investment platforms.

This is the ad they used in IPL - April 2021.

The value proposition is, low investment, flexibility safety, security, trust - basically all the keywords you’d use if you wanted to position a standard investment product.

And here is the TV ad they evolved to in Oct 2021

The message has now completely changed. The audience they position it for is closer to an India 2 youth, with the clear message of “change”. The sub-text is this - Use crypto as a way to ‘change your circumstances’. Of course, there is no mention of the high risk associated with crypto.

And this messaging worked - in a country where 3% of the population invests in stocks, a UNCTAD report suggested that 7% of the population owned crypto in 2021! My hunch is that this surge was driven by new users, who were looking at crypto as a variant of a get-rich quick scheme. Alas, a combination of government regulations and the market crash killed that option - and in hindsight, the government stepping in late 2021 to warn participants of taxation and incoming regulation probably reduced the extent of the pain that the retail crypto investor could have been put through.

But consumer demand finds a way. Where crypto lost out, we now have a new entrant.

Back to The Future(s)

This fantastic article in Economic Times gives a great background for the options trading boom in India.

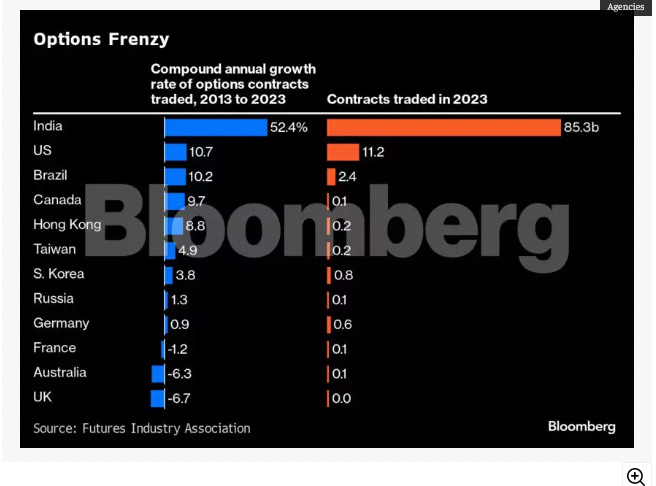

Between 2013-2023, the volume of options contracts traded has grown at a CAGR of ~50%. In comparison, the next best growth % was in the US - 10%

The volume of contracts traded in India is ~8x that of the US. The US, however, leads in value of contracts traded, and there lies the catch. The growth of contract volume shows that a large % of this growth has come from retail traders - 35% of options trades are made by retail traders in India.

Could this be for investment? No. The average time period a trader holds an option is less than 30 minutes. This is out and out speculation. And even this speculation is not working. 90% of retail traders lose money trading options and other derivatives, according to SEBI.

But that isn’t stopping the consumer. Everyone thinks they’re the one that can beat the house.

And where there is demand, there are people building businesses around that demand.

The obvious winners are trading platforms like Zerodha and Groww.

As of late 2023, Groww has 40m customers and 6.6 million active investors (invested once in the last 12 months). Its revenues for FY’ 23 are Rs 1227 (up 2.5x from FY ‘22), and has profit of Rs 448 cr. But, 80% of its revenues are from futures and options (F&O) trading, driven by the customer demand we talked about above.

Interestingly, Groww has the largest user base of active investors (6.6mn compared to Zerodha’s 6.4mn), but Zerodha’s revenues are 7x higher. Zerodha has grown through a trader community driven approach. This means its trader base is more active (despite being a similar number), and active traders contribute large % of volumes, and hence revenue (10% of active traders contribute 90% of trading volumes). So potentially, Groww’s user base is first time traders, being drawn in to trade risky F&Os. Will Groww be able to retain this user base or grow it considering the risk involved? This will be interesting to watch.

And where there is gold, there will be people selling shovels. Enter the ‘Options Influencer’ - people who encourage people to buy their courses as a short cut to untold riches (run a casual search on YouTube to understand the depth of this demand - there are 10s of such creators, with millions of subscribers). The good thing is that SEBI has begun to crack down, hard.

Reel it, Feel it

Everybody wants to be a creator today - from the bored housewife in Meerut, to the Class 10 student in Vizag, to the 70 year old kirana store owner in Surat. Social media is now second nature to Indians, and its resulting in an explosion of content on popular platforms. This is helped along by YouTube, which has played a big role in educating creators on how to grow and monetise themselves.

But what the bandwagon of creators joining the dominant platforms of today don’t know is that there is a brutal power law in monetisation. The top 0.1% of creators make most of the money that comes into this sector. On top of this, the rapid improvement in AI generated content is likely to ensure that entrenched creators with brand continue to generate most of the engagement, and it becomes progressively tougher for newer creators to grow.

Once again, high risk, low probability outcomes.

Ready Player One

And last, but definitely not the least, how can we forget ‘real money gaming’ aka ‘fantasy gaming’ aka ‘skill based gaming’ - different monikers that the industry uses to differentiate itself from gambling.

Everybody knows this is a large market, accounting for around Rs 13,500 crore in revenues in 2022. Founders built large companies, raised billions of dollars, showed fantastic user and revenue growth, and even profits! (all of which is unheard of Indian startup circles).

Gameskraft posted a profit of Rs 937 crore on revenues of Rs 2,112 crore in FY22 while fantasy sports major Dream11 posted a net profit of Rs 142 crore on operating revenue of Rs 3,841 crore in the same period.

The sector is today dealing with India’s taxman, which sometime in 2021 decided to take their blindfolds off. They had seen enough of ‘real money gaming’ and it was a little too close to ‘gambling’ for their comfort. Enter 28% GST and retrospective tax notices, and lots of cases in India’s famed legal system. An entire sector’s fortunes now hinge on how the apex court rules. You could argue that the tax action is harsh, but on the other hand regulatory clarity is better in the long run for an industry than leaving things to chance (there’s a wonderful irony here for a sector which tries its best to obfuscate the difference between chance and skill).

And that’s that

The preference for high-risk, low-probability games in India is more than just a quest for quick wealth; it's also mirror to the collective psyche of a society navigating through layers of socio-economic challenges. Whether driven by hope or desperation, this phenomenon is a critical aspect of consumer behaviour in India, and offers a window into the dreams and disappointments of this country.

As India continues to evolve, so too will the patterns of risk-taking among its people. Understanding these behaviours is crucial for policymakers and those looking to build businesses, as they navigate the complexities of a nation at the crossroads of tradition and modernity.

The high stakes of high-risk gambles are a testament to both India’s aspirations and its anxieties.

Until next time.

Interesting article. Wrote a response on medium.

https://medium.com/@dataWriter/response-high-risk-games-c8f0c919a801?sk=d57082be6bc4e1004ecce945e03a7f43

Brilliant article... Urban India doesn't understand how class and caste privileges work...On the UPSC and other entrance exam aspirants, one student mentioned that they attempt 6 times to get their parents and relatives off their back.. They are down in the dumps.. .they know it but they use the multiple attempts excuse... its more acceptable to society... we are definitely a country of multitudes every 100km